LWF runs 34 schools in Kakuma refugee camp in north-western Kenya where it applies a concept of inclusive education whereby students with disabilities are being welcomed into the same classrooms as non-impaired students.

Teacher James Lobalu, from South Sudan, shows Wuor Gai, who is blind, a drumming rhythm. All photos: LWF/Albin Hillert

Breaking stigma around disabilities

A visual or hearing impairment is no reason to deny a person education. This is the strong message that The Lutheran World Federation (LWF) schools in the Kakuma refugee camp send with their program to include students with disabilities in their classrooms.

LWF runs 34 schools across the four sections of Kakuma refugee camp in north-western Kenya, including 13 pre-primary and 21 primary schools. With more than 200,000 refugees currently residing in the camp, a single school can host thousands of students across a wide age-range.

Peace Primary is one such school – currently hosting close to 4,000 students aged 6-60 and across grades 1-8 – which applies a concept of inclusive education whereby students with disabilities are welcomed into the same classrooms as non-impaired students.

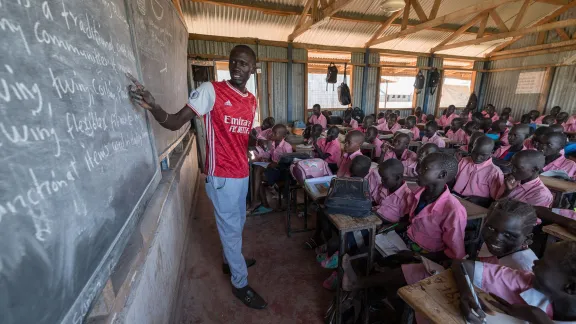

Teacher James Lobalu, teaches a class of fourth-graders at Peace Primary School. Photo: LWF/ Albin Hillert

“Disability cannot stop me”

Head teacher Jacob Nating’a explains that the concept first started at the school in 2018. “We provide inclusiveness for all learners to be in the same school, the same class, with the same teacher and only some differences in learning equipment,” Nating’a says.

In the past, disability has been a stigma in some communities in and around Kakuma. There are various superstitions associated with disability. Consequently, some of these children were hidden at home; their education was not prioritized in the family. More than once, LWF staff found children locked or tied up, so they would not run away.

Wuor Gai sits at his Braille typewriter. Photo: LWF/ Albin Hillert

Sometimes, students with disabilities would be enrolled in special classes – combining those with a cognitive disorder with students who had physical impairments. Consequently, the curriculum did not meet the potential of the students.

Spirit of responsibility

LWF helped change that situation. Now, “LWF community mobilisers go door to door to find these children, then talk to the parents about the programs that are available “, says Mary Obara, LWF Kenya Program Coordinator. While the children undergo a medical examination and are later enrolled in school, the parents join peer groups where they can share and learn from each other. LWF provides input on how to deal with everyday situations and provides the transport to school and school uniforms.

Class is underway at Shabele Primary School, taught by teacher Rogers Juma (right) and with sign-language interpretation given by Learning Support Assistant Amiza Lumumba (left). Photo: LWF/ Albin Hillert

Including these students in the regular classes and giving them the technical assistance needed to follow a regular school curriculum is a crucial step to break the stigma, head teacher Nating’a says. “This helps learners see that ‘this disability cannot stop me from achieving what I want’. They see that they can make it in life,” he adds.

Long-term, this will make a big difference, and we can have teachers too with disabilities in the future.

Jacon NATING’A, LWF head teacher, Peace Primary, Kakuma

“But there is also a spirit of responsibility to this, with non-impaired students becoming the helpers who make sure those with disabilities can keep up with their tasks. Long-term, this will make a big difference, and we can have teachers too with disabilities in the future,” Nating’a reflects.

Being accepted as normal

One who experiences the inclusive practices at Peace Primary school is 24-year-old student Wuor Gai, who is without eye-sight. He is older than his fellow students, like refugee students whose education was interrupted because of the conflict they fled from, but now want to take the chance to learn.

A refugee from South Sudan, Gai arrived in Kakuma from Juba with his aunt in 2016, and says he went to a different school before starting in Peace Primary. “This school is different,” Gai says, who uses a braille typewriter, while the other students in his class practice handwriting. “When I finish school, I want to become a teacher.”

And while applying a concept of inclusive education can be life-changing for individual students, there is also a long-term gain expected at a broader level from applying inclusive education, says Atieno Fellian Dorcas, the head teacher of Shabele Primary School. The school has just over 3,000 students, among them a group of hearing-impaired students taught with support from a sign-language learning assistant.

“The important thing is to avoid issues of stigma, for other learners to accept these students’ disability not as something strange but something normal. This way they will also accept them in society long-term,” she says.

LWF currently teaches 2,174 students with disabilities in Kakuma’s Primary schools. Another 245 children with disabilities attend preprimary or early childhood development institutions managed by LWF.