Land mines are a sad inheritance of the Colombian civil war – and they continue to mutilate and kill. LWF in Colombia, together with FELM, raises awareness about the danger and supports people after land mine accidents.

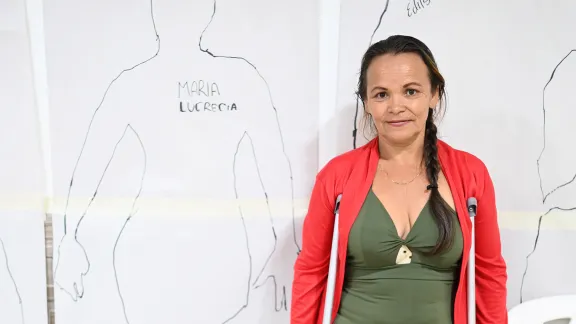

Maria Lucrecia lost her husband, one of her four sons and one of her legs in a mine accident. Photo: FELM

"A bridge between death and life”

(LWI) - "A land mine is the most effective soldier that can be found in our country - it doesn't sleep, it doesn't eat and it never stops being dangerous." This phrase was heard several times at a meeting of mine survivors in Arauca, Colombia, on the border with Venezuela. The meeting organized at the end of last year was part of a joint project between the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) and Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Mission (FELM). LWF and FELM in Colombia collaborate to prevent mine accidents and support those who survive them.

Invisible time bombs

Land mines in Colombia are the legacy of more than 50 years of civil war. Although Colombia has ratified the Ottawa Convention that bans anti-personnel mines, the number of mines in Colombia is increasing. Military groups (which were not part of the peace deal in 2016 between the Colombian government and the FARC) continue to use them in their fight over drug supply routes and territory.

"The 2016 peace agreement was supposed to reduce the number of landmines, but new armed forces have been created after the peace agreement to fight for the occupation of territories, and more landmines are being found every year," says Lorena Acevedo, LWF Colombia’s director of operations for the provinces of Arauca and Casanare.

Together against land mines: Vanessa Vallejo Velásquez, the project's coordinator, and Angela Villamizar hope to be able to organize more peer-to-peer meetings for survivors across Colombia and to raise more public discourse about the reality shaped by landmines. Photo: FELM

The difficult secutity situation in these regions hinders the de-mining work. At the same time, people displaced by the civil war have started to return to their old homes – which sometimes are no longer safe.

According to a report by the Red Cross, there were 43 percent more mine accidents in the province of Arauca in January-June 2022 than at the same time last year. While during the conflict, land mines would affect mostly eope in the armed forces, according to Land Mine monitor, 60 percent of landmine victims in 2022 were civilians.

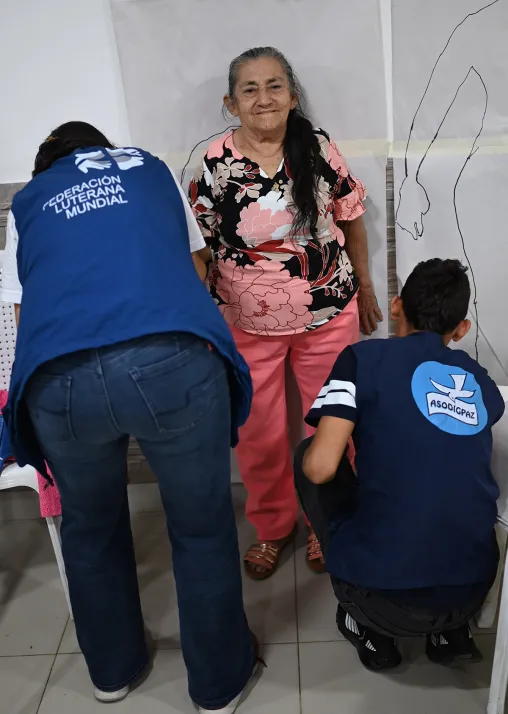

Blanca Galdera, 79 years old, lost the ability to walk, hear and smell in the explosion twelve years ago. Photo: FELM

The number of internally displaced people (IDP) in Arauca also increased from a little over 700 people to 11,000 people.

Landmines don't care about conventions. They remain underground for decades and are ready at any moment to destroy the lives of innocents.

Vanessa Vallejo VELASQUEZ, LWF Colombia project coordinator

"Landmines don't care about conventions. They remain underground for decades and are ready at any moment to destroy the lives of innocents", adds Vanessa Vallejo Velásquez, the LWF project's coordinator.

Life-changing accident

Every mine survivor remembers the time of their accident precisely. One of them is Maria Lucrecia. Ten years ago, in early April, she went for a walk on the outskirts of Saravena with her husband, two sons and their dog. The family noticed strange-looking cables on the ground. The dog walked ahead of the group to sniff a strange object when it suddenly exploded.

Lucrecia woke up after the explosion and saw her husband lying on the ground. She tried to ask if he was okay, but passed out again. The next time she woke up, 12 days had passed and she found herself in a hospital, learning that she had lost one of her sons, her husband, and a leg.

The road to recovery has been difficult, and she found it hard to accept the new reality at first. She says that she draws strength from her children and their dreams.

In November 2022, mine accident survivors gathered together in the city of Arauca. Photo: FELM

After the accident, she also came into contact with the Asodigpaz, a non-governmental organization of landmine survivors founded in connection with the LWF project. "They took me in like a daughter, and I understood that we can't move forward if we always look back. We must also remember to smile. I feel good when I get to tell my story, it feels like I'm freed from pain by sharing," Lucrecia says.

A bridge between death and life

The LWF project that FELM supports increases Colombians' awareness of the existence of mines and how to be aware of them in everyday life. Survivors have been educated about their rights and the state support they are entitled to, which includes crisis management, hospital treatment, provision of prostheses and legal support.

Psychosocial support has been an essential part of the project. Colombia is a pioneer project in offering such support to survivors. The third part of the project has been the establishment and support of the survivors' own associations and institutions, such as the Asodigpaz organization, founded in 2014, that Maria Lucrecia attends.

"Our organization is like a bridge between death and life. It invites us to understand that life doesn't end in an accident - despite everything, we're here, we keep going" says Guillermo Murcia, the organization's legal representative.

Building peace

At the end of 2022, the project supported by FELM in Arauca ended after seven years. Asodigpaz, the organization of the survivors of Arauca province, continues to operate independently. Velásquez is particularly excited about the work started last year with young people, focusing on psychosocial support for young survivors of mine accidents. Young people often find it particularly difficult to accept their changed life situation and the loss of their plans for the future. Therefore, they need a lot of support, especially right after the accident.

"For the future, it is very important that mine accidents gain more visibility in the public debate and that accidents and the risks caused by explosives are more generally taken as part of building peace in our country," says Velásquez.

Angela Villamizar, Arauca's expert on psychosocial support for the project, finds that the psychosocial support has significantly improved the lives of the survivors. "If before I felt sadness and pity for the survivors, now the dominant feeling is respect and admiration. They are so much more than survivors of mine accidents; they are individuals who build peace in our country."